Despite being too small to be seen by the naked eye, or even an optical microscope, viruses affect our daily lives and shape the course of human history. Viruses can give us anything from a simple runny nose (e.g., rhinovirus), to a gory death (e.g., Ebola, Marburg, and other hemorrhagic fevers), to a radically new way of working and connecting with each other (e.g., SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes covid). This staggering diversity of potential comes from just a bit of genetic material cleverly packaged in a coating of protein. Why is it that, although they are strikingly similar in design, some viruses cause symptoms too minor to notice, while others turn us into a human-sized bowl of Campbell’s soup?

As we might expect, we can thank natural selection for these different outcomes. But how does natural selection make some viruses vicious killers, and others just an annoyance? To understand the details, let’s start with what a virus is, how a virus works, and what a virus wants.

What is a virus and how does it work?

Viruses are biological machines that can only reproduce inside the living cells of an organism. While viruses have existed since the beginning of life, and have infected humans since before we were human, they were only scientifically discovered in the late 19th century as an infectious agent that was smaller than any living cell.

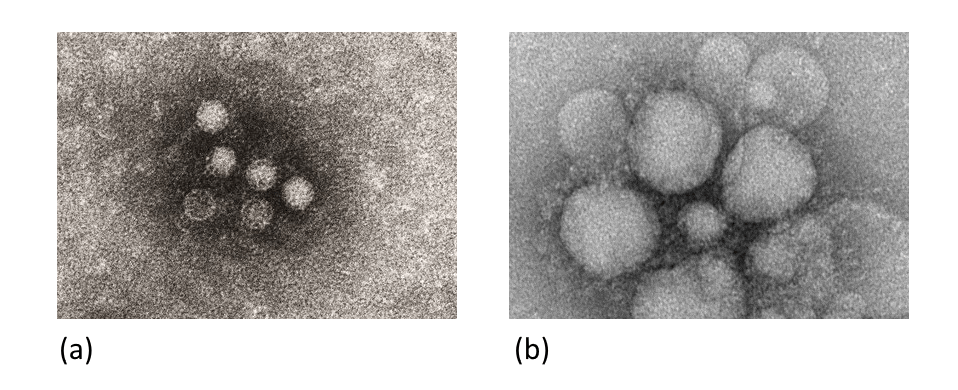

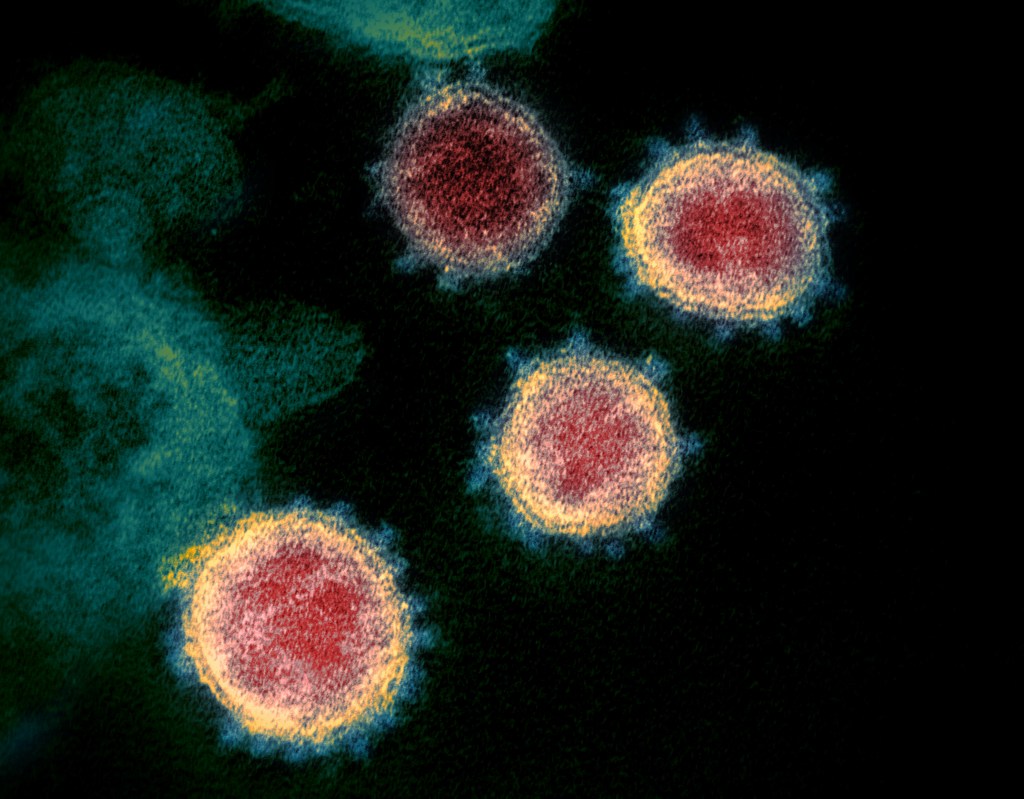

While individual viruses may look different, they share a few basic similarities. Each virus contains genetic material in the form of nucleic acids, though these may be anything from single stranded RNA to double-stranded DNA. Viral genomes are typically short, from about two-thousand base pairs to one million base pairs (compare that to the human genome, which is more than six billion base pairs). This genetic material is surrounded by the capsid, a layer of proteins that protect the nucleic acids while the virus travels through the environment. Viruses may also have a viral envelope – a coating of cell membrane from the cell the virus used to replicate.

Because a virus lacks the capability to reproduce on its own, it must hijack the reproductive capabilities of another cell. An infecting virus will use its surface proteins to merge through the cell membrane of a host cell. It will then begin the process of making copies of itself, using the unsuspecting organelles of the host. Eventually, the host cell bursts and new copies of the virus are released and can infect other cells, either in the same host or a new one.

What does a virus want?

Successful viruses reproduce. If a virus can be said to have a want, that want is only to make more copies of itself. Any damage a virus does to its host (e.g., provoke an immune response, damage tissues, cause death) is just the cost of doing business. Natural selection rewards the virus that reproduces and eliminates the virus that doesn’t.

Broadly, there are two strategies a virus can use to make copies of itself. First, it can maximize the number of copies it makes during its replication cycle – quickly infecting every possible cell in a host and filling them to bursting with virus. While this strategy helps a virus multiply quickly, it can often damage or kill the host organism. The second strategy is to minimize damage to the host (i.e., make fewer copies during replication or do so in a less harmful way), but infect lots of different hosts.

Unfortunately for viruses (but fortunately for us), these two strategies operate at odds with each other. High virulence means the host often dies, preventing contact with other healthy hosts that the virus may spread to. High transmissibility means that the host must survive well enough to contact other healthy hosts, limiting the rate of viral replication to avoid damaging the host. The virus makes a trade-off between replicating in a host, and replicating between hosts.

We can also describe this tradeoff in terms of microbiology. Viral load, the number of copies of a virus present in a host, can be considered a rough proxy for transmissibility. The more densely packed a host is with virus, the more likely it is for them to shed a copy of the virus that can go on to cause another infection. As a virus replicates more to become more infectious, it actually limits its transmissibility by killing its host too quickly.

A third way to think of this tradeoff is simply considering the implications of each strategy. A virus could be (a) both highly virulent and highly transmissible, (b) highly virulent or highly transmissible, or (c) neither highly virulent nor highly transmissible. If a virus evolves into option (a) it ends up killing its host population, dooming the virus and its host to extinction. If a virus evolves into option (c), it fails to reproduce and also goes extinct. Viruses can only persist if they evolve into option (b), and exist somewhere on a spectrum between highly virulent and highly transmissible.

Viruses in the real world seem to adhere to this trade-off. As we see in Figure 3 viruses are either very deadly and not very contagious, or very contagious and not very deadly.

Why do viruses pick one strategy or the other?

The trade-off model described above shows that viruses can be successful by being highly virulent, highly transmissible, or somewhere in between. But it gives no insight into why a virus would be one way or the other. To understand how natural selection leads a virus to a particular strategy, let’s consider examples from each.

The Ebola virus is one of the most deadly viruses known to humanity. First identified infecting humans in 1976, Ebola is a zoonotic virus – it originated in an animal (likely a bat or non-human primate) before infecting humans. The virus is suspected to make the jump to humans during the production of “bushmeat” – raw or minimally processed meat from infected bats, monkeys, cane rats, or antelope. During an Ebola outbreak, mortality rates can exceed 90%. Viral loads in patients that die of ebola often exceed 10 million virus copies per milliliter of whole blood, more than ten times the viral load for the common cold. This tremendous replication is part of the reason Ebola is so deadly, and also part of the reason it can be contained: the virus kills its host before they can infect others.

On the opposite end of the spectrum is hepatitis B, a virus that chronically infects the liver. Genetic analysis of hepatitis B suggests that it began infecting humans approximately 8,000 years ago. Hepatitis B causes death in less than 1% of the infected population, and over the long term, people infected with hepatitis B can have viral loads in the tens of thousands of copies per milliliter (a factor of one thousand less than Ebola). However, hepatitis B is far more transmissible than Ebola – each infected person will, on average, go on to infect five other people1 (2.5 times more than Ebola).

The law of declining virulence

A striking difference between these two viruses is how long they’ve been infecting humans. Ebola is zoonotic and a relative newcomer, only having been known for about 50 years. Hepatitis B is an old friend and has been with us since antiquity. The obvious hypothesis is that mortality decreases as the time since emergence of the virus increases. The longer a virus has been infecting us, the less deadly it becomes.

This idea is called the “Law of declining virulence,” and is popularly attributed to Theobald Smith, who articulated it in the late 19th century. We can understand it with a thought experiment. Imagine a new virus shows up in a densely populated region of healthy people. Because the dense population makes infecting new hosts easy, there is little evolutionary pressure for the virus to evolve more transmissibility. Instead, the biggest boost comes from replicating more, and therefore being more lethal. As the virus infects and kills, the population becomes less dense, and transmission becomes harder. Now the most successful strategy is to trade some virulence for transmissibility – the virus kills less or more slowly, so that the virus can spread to more hosts. This process of decreasing virulence and increasing transmissibility continues until the population is reduced to a critical value where any change in virulence or transmissibility reduces the ability of the virus to reproduce. What started as a rare and deadly killer is now a common annoyance.

We can see this relationship if we plot the mortality rates of viruses against their time since emergence.

Noobs vs pros

The surprising conclusion is that the viruses that are so deadly to humans aren’t really that good at being viruses. Unlike tigers or sharks, viruses aren’t predators – they’re parasites. Their effectiveness isn’t measured by how well they kill. In a weird way, effectiveness is measured in how well they don’t kill, because the longer a host survives the more the virus can subscribe.

So Ebola and its 90% mortality rate? Total noob. But rhinovirus, the virus that causes the common cold and kills almost no one? What an absolute unit. That’s a pro virus.

The fine print

The above analysis assumes (1) the virus is transmitted by contact (e.g., bodily fluids), (2) the virus cannot survive outside the host for an appreciable period, and (3) host movement is restricted. For some viruses, these are good assumptions – for others, they are not. In the absence of these assumptions, viruses can sometimes evolve *higher* virulence. For example, viruses transmitted by vectors (i.e., by other organisms) can evolve and maintain high virulence in humans provided their virulence in their vector remains low.

Also, details of the reproductive number R0 of viruses can vary across outbreaks and be challenging to measure. For example, literature has measure the R0 for hepatitis B as low as around 1.5 and as high as 10. I’ve done the best I can with the data available, but there are uncertainties in all of the quantitative values I reference.

References

Cressler, C. E., McLeod, D. V., Rozins, C., Van Den Hoogen, J., & Day, T. (2016). The adaptive evolution of virulence: A review of theoretical predictions and empirical tests. Parasitology, 143(7), 915–930. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003118201500092X

Hay, S. I., Battle, K. E., Pigott, D. M., Smith, D. L., Moyes, C. L., Bhatt, S., … Gething, P. W. (2013). Global mapping of infectious disease. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368(1614). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0250

Visher, E., Evensen, C., Guth, S., Lai, E., Norfolk, M., Rozins, C., … Boots, M. (2021). The three Ts of virulence evolution during zoonotic emergence. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 288(1956). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.0900

Lenski, R. E., & May, R. M. (1994). The evolution of virulence in parasites and pathogens: Reconciliation between two competing hypotheses. Journal of Theoretical Biology. https://doi.org/10.1006/jtbi.1994.1146

Granados, A., Peci, A., McGeer, A., & Gubbay, J. B. (2017). Influenza and rhinovirus viral load and disease severity in upper respiratory tract infections. Journal of Clinical Virology, 86, 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2016.11.008

Berngruber, T. W., Froissart, R., Choisy, M., & Gandon, S. (2013). Evolution of Virulence in Emerging Epidemics. PLoS Pathogens, 9(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003209

Méthot, P. (2012). Why do Parasites Harm Their Host ? On the Origin and Legacy of Theobald Smith’s Law of Declining Virulence. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, 34(4), 561–601.

Furuse, Y., Suzuki, A., & Oshitani, H. (2010). Origin of measles virus: Divergence from rinderpest virus between the 11th and 12th centuries. Virology Journal, 7(52), 2–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-7-52

Margaret Littlejohn, Stephen Locainini, L. Y. (2016). Origins and Evolution of Hepatitis B Virus and Hepatitis D Virus. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory PRess. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a021360

Blanquart, F., Grabowski, M. K., Herbeck, J., Nalugoda, F., Serwadda, D., Eller, M. A., … Fraser, C. (2016). A transmission-virulence evolutionary trade-off explains attenuation of HIV-1 in uganda. ELife, 5 (November 2016), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.20492

H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza : Timeline of major events. (2014). World Health Organization, (December), 1–89. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/H5N1_avian_influenza_update20121210.pdf

Matson, M. J., Ricotta, E., Feldmann, F., Massaquoi, M., Sprecher, A., Giuliani, R., … Munster, V. J. (2022). Evaluation of viral load in patients with Ebola virus disease in Liberia: a retrospective observational study. The Lancet Microbe, 3(22), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00065-9

Morris et al., 2012. (2008). The Evolutionary and Epidemiological Dynamics of the Paramyxoviridae. J Mol Evol., 66(2), 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00239-007-9040-x.The

Henry, D. D., Ciriaco, F. M., Araujo, R. C., Fontes, P. L. P., Rostoll-cangiano, L., Sanford, C. D., … Dilorenzo, N. (2020). Possible European origin of circulating Varicella-zoster virus strains. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 12(1), 1–30. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.09.005%0Ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.060

Leave a comment